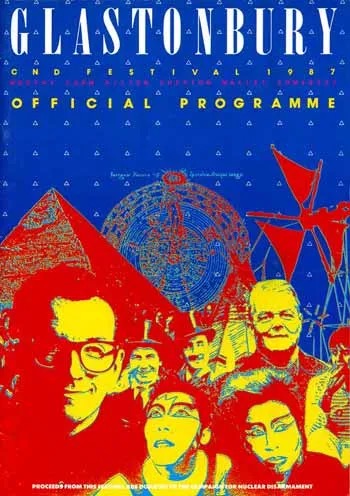

Glastonbury CND Festival 1987. Elvis Costello and Van Morrison were headlining. And in the Green Field, there was a display about animal testing, vivisection and industrial farming.

That was when I stopped eating meat. Well actually, it was around 11 am the following morning after a breakfast fry-up!

From that point, I never looked back. I’d always liked meat – particularly nice bloody, juicy steaks. But on reflection, it didn’t seem worth the price. Once I’d made that decision, it was surprisingly easy to stick to it, and I never wavered.

It wasn’t that I disagreed with the principle of eating meat – more that I found modern, industrial farming practices truly abhorrent. And the convenience of the pre-packed, cellophane-wrapped supermarket experience distanced us from the awful truth of how it got there. So we never even give it a second thought.

Thirty-odd years later, we have a problem. One that was always inevitable from the moment we agreed to take on the five chicks from the school hatching project.

Actually, I’m not sure I did ‘agree’ as such. In fact I recall a pretty firm “No!” featuring in that short conversation. However, the next day, there they were, a cardboard box with five cute, fluffy chicks inside.

It was great fun watching them grow. And they grew amazingly fast.

They were duly named according to our Star Wars convention:

- Lando Calchickien

- Jabba the Cluck

- BB-Egg

- Master Yolka

- Boba Peck

At that point it wasn’t clear how many girls we’d get from the five. But after a few weeks it was clear that the ratio was tipping the wrong way. This was a problem as apparently, boy chickens don’t lay as many eggs as girls.

The ‘smallholding’ thing was always something of an experiment. Part of which was to see whether we’d be able to kill and eat animals that we’d raised. For someone who hadn’t eaten meat for three decades, this was a pretty big deal.

I had a feeling that phase of the experiment was looming.

Warning: In the post below, there are pictures of chicken plucking and evisceration. If this isn’t your thing, please feel free to pass on by.

Fast forward a few months and Jabba the Cluck was strutting around like he owned the place.

And then the crowing started. Awkwardly at first, in his adolescent, breaking-voice phase. And then, with more confidence. Regular as clockwork. And yes, starting at four in the morning.

The neighbours didn’t complain at all – but it was probably just a matter of time. I was jumping at every crow, nervously expecting the call…

So it was time.

Some internet research led to the construction of a killing cone – made from a plastic container, cut down one side and then ‘stitched’ into a cone with the aid of some cable ties. The idea is the cone holds the chicken securely upside-down with the head and neck protruding underneath. This calms the bird and prevents any struggling and flapping. It also allows the blood to drain easily.

The deed was carried out in the evening. I separated Jabba from the rest of the flock and carried him back to the other end of the plot, well away from the others. I felt an enormous sense of responsibility – it was important to do this well. It needed to be as quick and painless as possible for Jabba. Walking back with him I was reflecting on life and death, and talking softly to him. Animals can sense your mood and I hoped this would help keep him (and myself) calm.

His legs were loosely tied together, then he was turned upside down into the cone.

Killing was performed with a firm cut of a razor sharp knife. I remember the blood being warm on my hands as it drained into the bucket. His legs kicked a bit and then he was quiet.

It has to be said, the cone did its job perfectly.

It’s strange – as soon as he was dead, he was just a bit of meat.

Plucking was easy.

With the feathers removed he became ‘chicken’ as opposed to a chicken.

Evisceration was a cautious process – remembering everything from the YouTube videos, trying not to cut through the intestine (which would have spoiled the meat with faecal matter. But it was surprising how easily the insides came out intact.

Despite my lack of familiarity with meat products, it was easy to recognise the heart, liver, lungs.

The large, white kidney-shaped organs were puzzling at first. We hadn’t seen them on the chicken evisceration videos we’d prepped on*.

Yup, you guessed it. Rooster testicles. And look at the size of them… bigger than his heart. That explains a lot. Whilst they’re a delicacy in some places, I’m afraid they went in the scrap bin – which was then fed to the red kites we have around here. That’s a sight in itself, seeing these impressive birds swooping down to pick up the entrails. For another time…

*Of course, the chickens in the butchering videos had been females…

The gizzard is a muscly organ in the early part of the digestive tract. Food is held along with bits of grit and gravel in a bag inside the gizzard which contracts, using the gravel to grind up the food. It’s why chickens don’t need teeth. The gizzard is edible – it’s carefully cut open so as not to cut into the food sack. It peels apart really easily.

There is room for improvement with my butchering skills. But eventually I got there. Three freezer bags marked “Jabba”.

With even less experience of cooking chicken, preparation was subcontracted. The legs went in the oven with tomatoes and potatoes. The carcass made Yakhni – chicken broth made with onion, ginger, garlic, clove, cinnamon, cumin, bayleaves, and black cardamon. The offal was fried quickly in butter.

Eating chicken for the first time in thirty years felt surprisingly familiar. Gnawing the meat from the bones seemed second nature. It tasted great! The meat itself was a lot darker than the stuff you see on the supermarket shelves. I’m not sure if that’s because it was a rooster. I imagine diet and exercise are factors too.

A couple of weeks later, Boba Peck and Master Yolker had eased into the space left by Jabba. Then Boba got carried away with the power, chased our 7 year old nephew around the chicken run, pecked him on the leg, and drew blood! That I’m afraid, sealed his fate – and the next day Boba and Master Yolker went into the cone…

So, what have I learned from this exercise?

- Yes, I can kill chickens.

- Home-reared chicken tastes good. I’ve no idea what modern, intensive chicken tastes like, but according to others familiar with the matter, it’s a world apart.

- A lot of effort goes into in killing, plucking, and preparing a chicken. Sure, familiarity would speed up the process, but even with practice this is not something I could ever take lightly.

- When you’re this close to the source of your food, and experience the end to end process from newborn chick, through to adulthood, and then the taking of its life, you truly appreciate its value.

- Add in your own hard work in raising and looking after them, and the value increases further.

- With the clarity that results from this, you make damn sure nothing is wasted. (Ok – apart from those testicles – but I’m sure the kites appreciated them.)

- Despite the effort, I wouldn’t feel comfortable subcontracting the process to someone else. This is a necessary part of the whole smallholding thing. These are skills and knowledge we should have.

Despite this experience, I don’t feel the need to start buying and eating meat again. I still can’t justify the true cost to get to the finished product on your plate. Equally, I don’t see us intentionally rearing birds for the table anytime soon. That might change one day, but for now I’m happy to continue with my mainly vegetarian diet, with fish now and then.

The process has reinforced my views about abhorrent industrial farming processes. The cheap chicken you see in supermarkets, fast food joints, butchers and halal meat shops is only possible by adopting terrible practices that deny chickens their basic needs. I believe this is cruel, unnecessary, and unethical. If you’re buying a whole chicken for 3 quid, you can be assured it’s endured a pitiful life.

Organic certification indicates greatly improved animal husbandry, and the price of organic chicken (in the range £12 – £16) reflects what it really costs to raise a table bird. Probably the best source of meat is from small farms and smallholdings where chickens are raised in as natural a way as possible. These smaller operations usually can’t afford organic certification – but will often be happy to show you around.

This is my experience. My journey into the normally hidden world of animal slaughter.

I’m not suggesting everyone should become vegetarian or vegan. I would however highly recommend becoming more aware of the source of your food, the way it’s reared or grown – and the process it goes through before it hits your plate. Industrial farming has turned chicken into a mass produced commodity. It’s easy to grab it from the supermarket shelf and treat it with as much value as a bag of potatoes.

As a nation, we eat an unhealthy amount of meat – and suffer the consequences in terms of record levels of obesity and disease. ‘Organic’ isn’t something new – it’s pretty much how all chicken used to be before the 1950s when intensive farming took off. The cost of organic produce is often cited as a blocker – but you may end up paying in a different way further down the line. One solution is to spend the same, buy quality, don’t waste any of it, and eat it less often!